Session 10 - Step 3 in TCM

Reminder: TCM steps

- Identify definitions of constructs and relevant phenomena

- Formulate a prototheory: Create a VAST display

- TODAY: Develop a formal model

- Check the adequacy of the formal model

- Evaluate the overall worth of the constructed theory

Step 1: Define variables

Define a variable for each construct of the VAST display. These can be measured variables or internal, unmeasured variables. You can either refer to an actual measurement procedure or simply define a variable. In both cases you should explicitly define the following properties:

- scale level (categorical, ordinal, interval scale),

- range of possible values (e.g., 0 .. 1), and

- semantic anchors (e.g., 0 = “complete absence”, 1 = “maximal possible value”)

Some guiding questions and heuristics

- Scale level of measurement (Stevens’s typology):

Nominal → Ordinal → Interval → Ratio - Is the variable naturally bounded? On both sides or only one?

- How can the numbers be interpreted?

- Natural/objective scale (e.g. physical distance)

- As standardized z-scores?

- Normalized to a value between 0 and 1? Or rather -1 to 1?

- Can we find an empirical or semantic calibration?

- Just noticable difference

- 100 = “largest realistically imaginable quantity of that variable”

Example

| Construct in VAST display | Scale level | Range/values | Anchors |

|---|---|---|---|

| Affective tone of instruction | Continuous | [-1; 1] | -1 = maximally negative 0 = neutral +1 = maximally positive |

| momentary anxiety | Continuous | [0; 1] | 0 = no anxiety 1 = maximal anxiety |

| … | … | … | … |

Deliverable:

Create a table with all constructs and accompanying variable definitions in your VAST display.

Step 2: Define functional relationships between variables

Every causal path needs to be implemented as a function, where the dependent variable/output \(y\) is a function of the input variables \(x_i\).

\(y = f(x_1, x_2, ..., x_i)\)

This can, for example, be a linear function, \(y = \beta_0 + \beta_1x_1\). As this is unbounded, however, it can easily happen that the computed \(y\) exceeds the possible range of values.

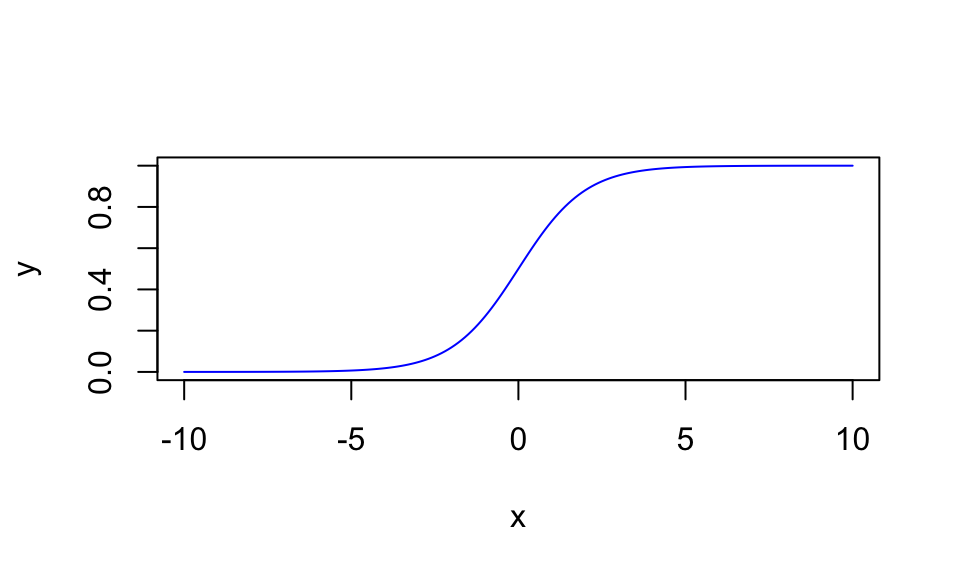

Tool 1: The logistic function family

If \(y\) has defined boundaries (e.g., \([0; 1]\)), a logistic function might be a convenient function, as it automatically bounds the values between a lower and an upper limit (in the basic logistic function, between 0 and 1): \(y = \frac{1}{1 + e^{-x}}\).

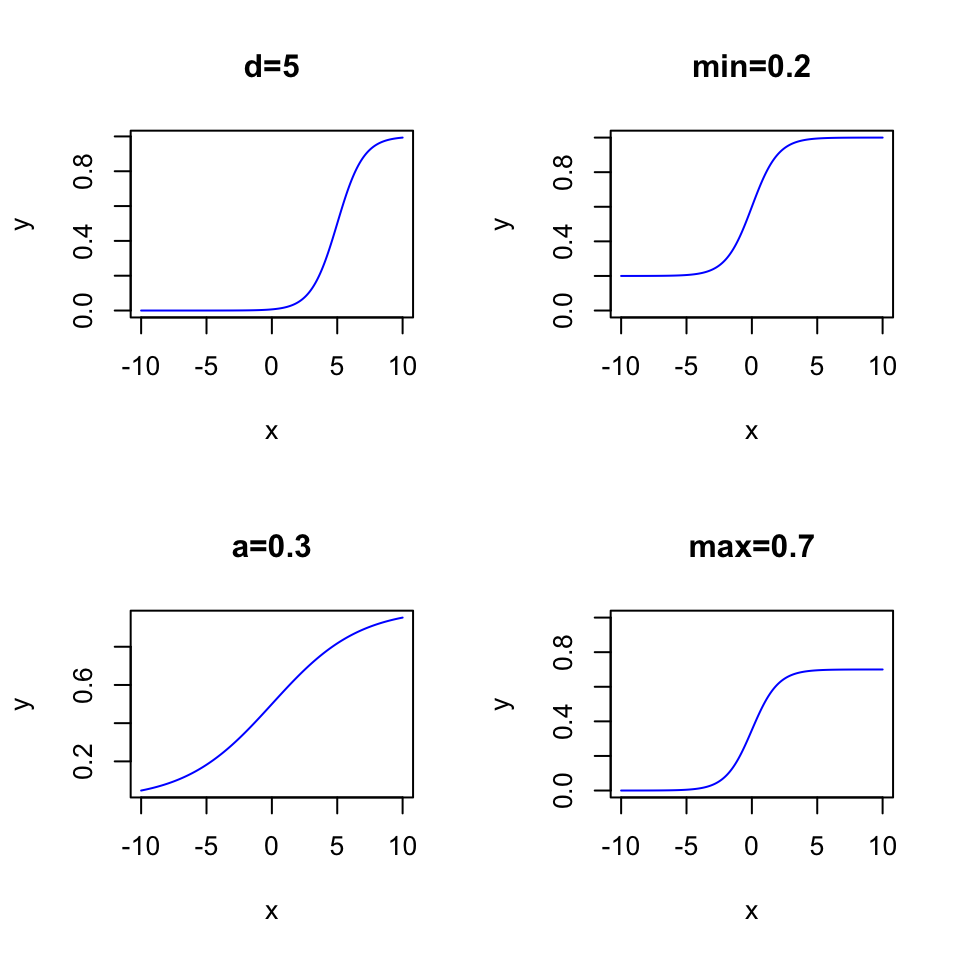

With the 4PL model from IRT, you can adjust the functional form to your needs, by:

- shifting the inflection point from left to right (aka. “item difficulty”, parameter \(d\))

- change the steepness of the S-shape (aka. “discrimination parameter”, parameter \(a\))

- Move the lower asymptote up or down (parameter \(min\))

- Move the upper limit up or down (parameter \(max\))

logistic <- function (x, d = 0, a = 1, min = 0, max = 1) {

min + (max - min)/(1 + exp(a * (d - x)))

}

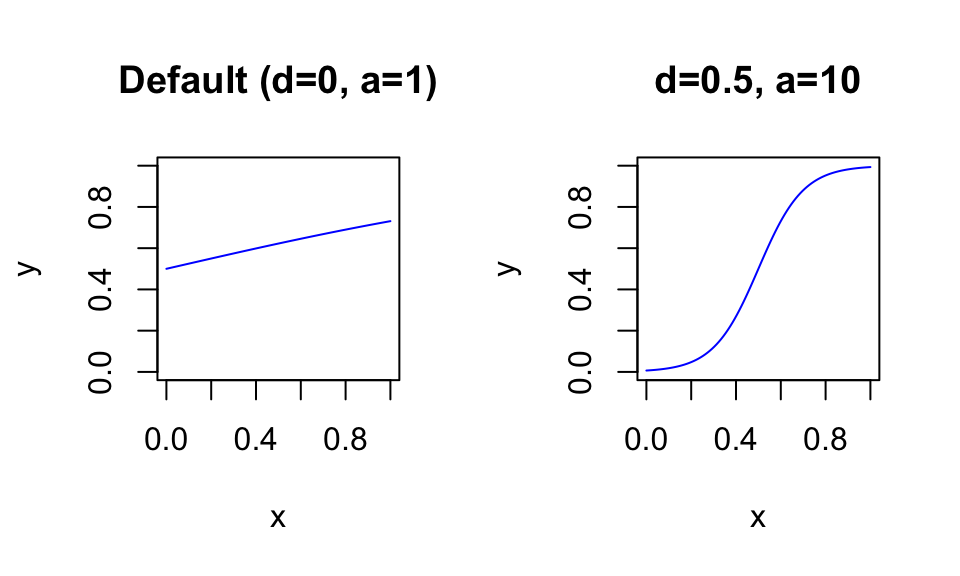

These parameters can be used to “squeeze” the S-shaped curve into the range of your variables. For example, if your \(x\) variable is defined on the range \([0; 1]\), the following function parameters lead to a reasonable shift:

Tool 2: The beta distribution

If you start simulating data for your virtual participants, you want to simulate their starting values. For example, the virtual participants might differ in their anxiety, which you previously defined on the range \([0; 1]\). How can you generate random values that roughly look like a normal distribution, but are bounded to the defined range?

For simulations, it is good to know some basic distributions. Here are three interactive resources for choosing your distribution:

- The Distribution Zoo by Ben Lambert and Fergus Cooper

- The Probability Distribution Explorer by Justin Bois

- Interactive collection of distributions by Richar Morey

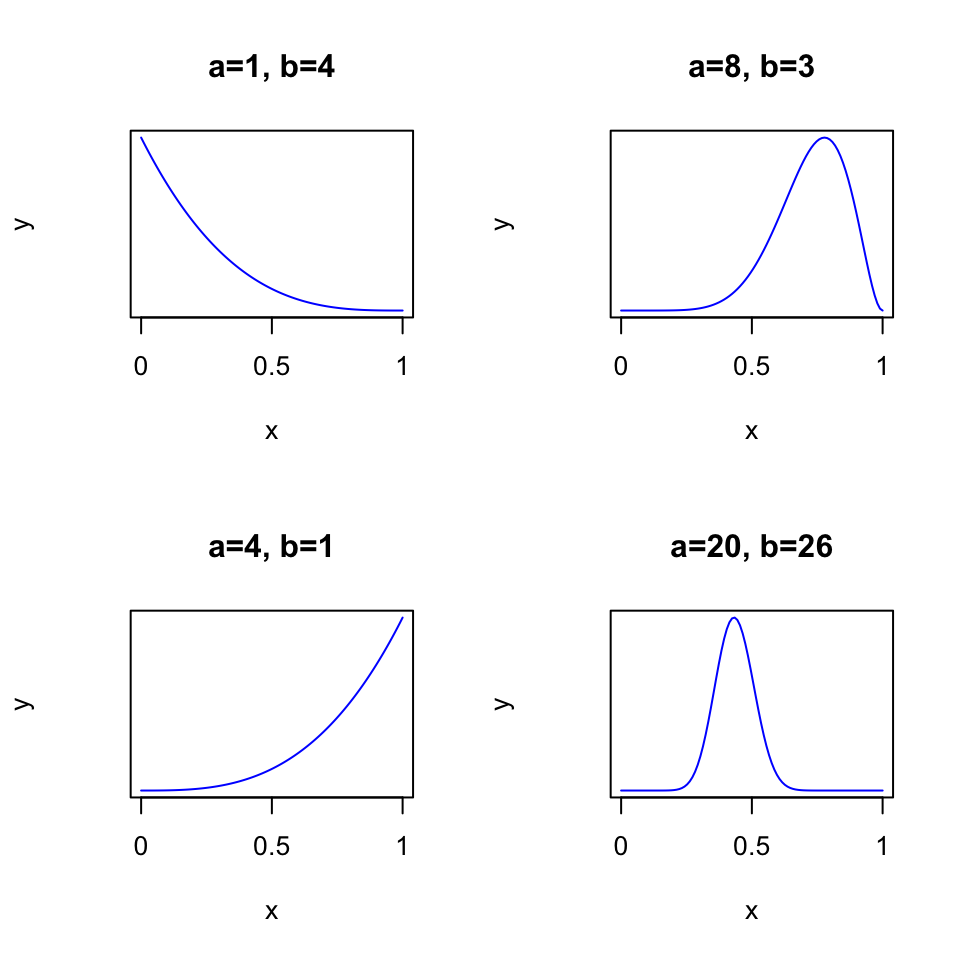

A handy distribution for the \([0; 1]\) range is the beta distribution. With its two parameters \(\alpha\) and \(\beta\), it can take many different forms:

Code

# Note: shape1 is alpha, shape2 is beta

par(mfcol=c(2, 2))

x_values <- seq(0, 1, length.out=100)

plot(x_values, dbeta(x_values, shape1=1, shape2=4), type = "l", col = "blue", xlab = "x", ylab = "y", main="a=1, b=4", xlim=c(0, 1), yaxt = "n", xaxt="n")

axis(side = 1, at = c(0, 0.5, 1), labels = c("0", "0.5", "1"))

plot(x_values, dbeta(x_values, shape1=4, shape2=1), type = "l", col = "blue", xlab = "x", ylab = "y", main="a=4, b=1", xlim=c(0, 1), yaxt = "n", xaxt="n")

axis(side = 1, at = c(0, 0.5, 1), labels = c("0", "0.5", "1"))

plot(x_values, dbeta(x_values, shape1=8, shape2=3), type = "l", col = "blue", xlab = "x", ylab = "y", main="a=8, b=3", xlim=c(0, 1), yaxt = "n", xaxt="n")

axis(side = 1, at = c(0, 0.5, 1), labels = c("0", "0.5", "1"))

plot(x_values, dbeta(x_values, shape1=20, shape2=26), type = "l", col = "blue", xlab = "x", ylab = "y", main="a=20, b=26", xlim=c(0, 1), yaxt = "n", xaxt="n")

axis(side = 1, at = c(0, 0.5, 1), labels = c("0", "0.5", "1"))

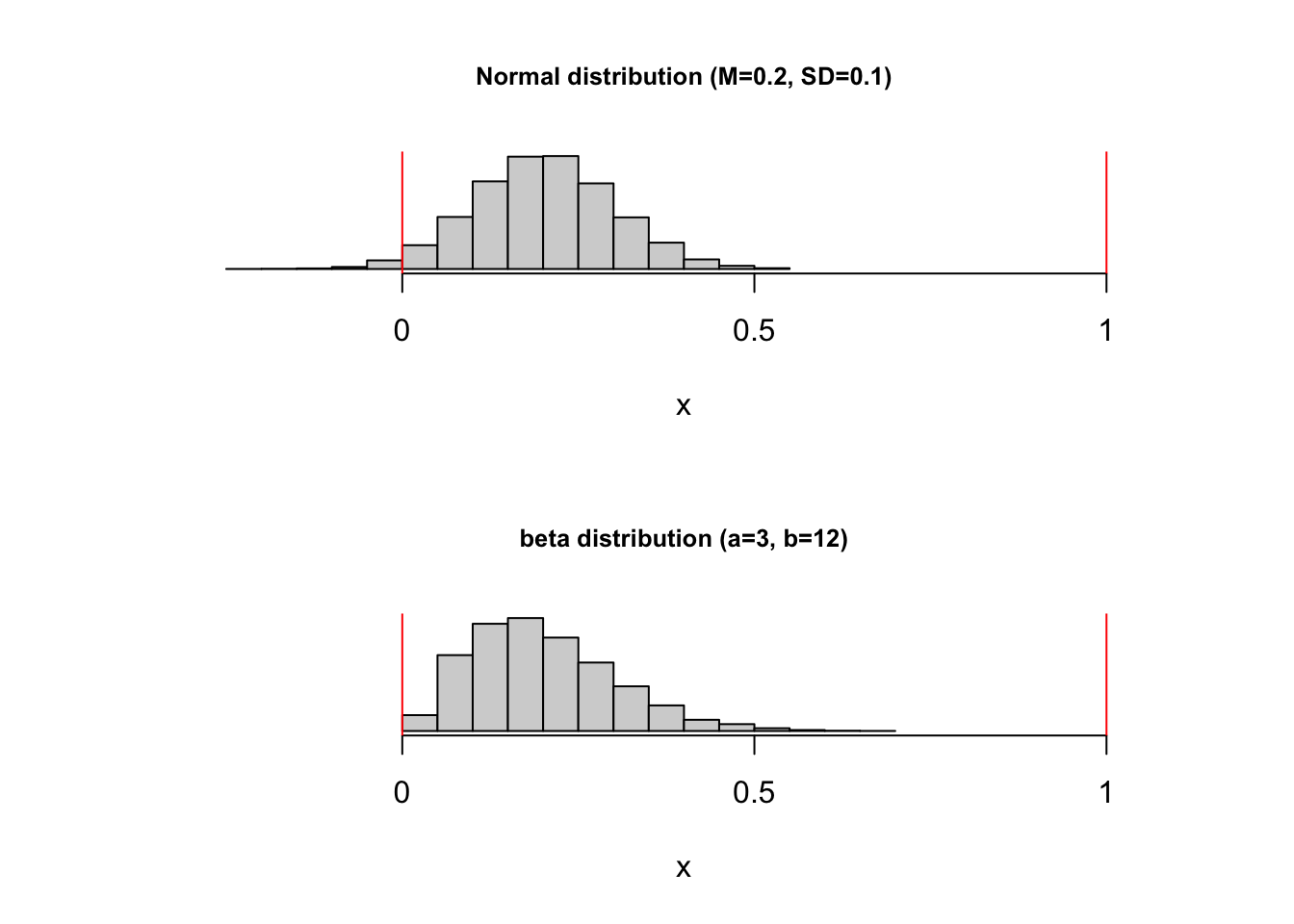

Assume that you intuitively started with a normal distribution with M=0.2 and SD=0.1 (rnorm(0.2, 0.1)) to simulate your values. But this function can generate values < 0 and > 1. How can you achieve a beta distribution that approximates the properties of this normal distribution? You can work out the math yourself (e.g., by looking at formula for the mean and the variance of the beta distribution) - or you can ask ChatGPT. After all, we only use this function as a tool to get some plausible values.

Here’s a possible plain language prompt: > “We have a normal distribution with mean=0.2 and SD=0.1. But the results should be bounded on a scale from 0 to 1. Create a beta-distribution that mimics the properties of the described normal distribution.”

The Wolfram Alpha plugin for ChatGPT gives this answer:

To mimic the properties of a specified normal distribution (with a mean and standard deviation) using a beta distribution within a bounded interval (in this case, 0 to 1), we need to find the parameters of the beta distribution (alpha \(\alpha\) and beta \(\beta\)) that match the mean and variance of the normal distribution as closely as possible. The mean \(\mu\) and standard deviation \(\sigma\) of the normal distribution are given, and the mean \(m\) and variance \(v\) of the beta distribution can be related to its parameters as follows:

- Mean of the beta distribution: \(m = \frac{\alpha}{\alpha + \beta}\)

- Variance of the beta distribution: \(v = \frac{\alpha \beta}{(\alpha + \beta)^2 (\alpha + \beta + 1)}\)

Given: - Mean of the normal distribution (\(\mu\)) = 0.2 - Standard deviation of the normal distribution (\(\sigma\)) = 0.1 - Hence, variance of the normal distribution (\(\sigma^2\)) = 0.01

We need to solve for \(\alpha\) and \(\beta\) such that: - \(m = \mu = 0.2\) - \(v = \sigma^2 = 0.01\)

Rearranging the formula for the mean \(m\) to solve for \(\beta\) in terms of \(\alpha\) and \(\mu\): - \(\beta = \alpha \left(\frac{1}{\mu} - 1\right)\)

Substituting \(\mu = 0.2\) and \(v = 0.01\) into the formulas, we can solve for \(\alpha\) and \(\beta\). Let’s perform these calculations.

The parameters for the beta distribution that mimic the properties of the described normal distribution (with mean = 0.2 and standard deviation = 0.1, bounded between 0 and 1) are \(\alpha = 3\) and \(\beta = 12\).

This beta distribution should closely match the shape and spread of the specified normal distribution within the bounds of 0 to 1.

You can generate random values with the rbeta function. Here’s a comparison of a normal distribution and a matched beta distribution that respects the boundaries \([0; 1]\):

Code

par(mfcol=c(2, 1))

hist(rnorm(10000, mean=0.2, sd=0.1), xlab = "x", ylab="", main="Normal distribution (M=0.2, SD=0.1)", yaxt = "n", cex.main = 0.8, xlim=c(-0.3, 1.1), xaxt="n")

axis(side = 1, at = c(0, 0.5, 1), labels = c("0", "0.5", "1"))

abline(v=0, col="red")

abline(v=1, col="red")

hist(rbeta(10000, shape1=3, shape2=12), xlab = "x", ylab="", main="beta distribution (a=3, b=12)", yaxt = "n", cex.main = 0.8, xlim=c(-0.3, 1.1), xaxt="n")

axis(side = 1, at = c(0, 0.5, 1), labels = c("0", "0.5", "1"))

abline(v=0, col="red")

abline(v=1, col="red")

Of course, this is just a start - you can use the full toolbox of mathematical functions to implement your model!

These considerations about functional forms, however, are typically not substantiated by psychological theory or background knowledge - at least at the start of a modeling project. We choose them, because we are (a) acquainted to it, and/or (b) they are mathematically convenient and tractable.

Empirical evidence can inform both your choice of the functional form, and, in a model-fitting step, the values of the parameters.

Deliverable:

Create a table with all functional relationships. Use the IDs from the VAST display to create an unambiguous connection between both documents.

Step 3: Implement the functions in R

Do “atomic” functions: Each R function implements exactly one functional relationship

Document all input parameters of your functions, and say what the function computes. This is ideally done inlien in the code, so that the documentation is right there where you need it. In R, this can be done with the established roxygen2 documentation standard:

#' Compute the updated expected anxiety

#'

#' @param momentary_anxiety The momentary anxiety, on a scale from 0 to 1

#' @param previous_expected_anxiety The previous expected anxiety, on a scale from 0 to 1

#' @param alpha A factor that shifts the weight between the momentary anxiety (alpha=1) and the previous expected anxiety (alpha=0) when the updated expected anxiety is computed.

expected_anxiety <- function(momentary_anxiety, previous_expected_anxiety, alpha=0.5) {

momentary_anxiety*alpha + previous_expected_anxiety*(1-alpha)

}Next, connect all functions to one “super-function”, which takes all free inputs as parameter and compute the focal output variable(s).

Test the super-function:

- Enter some reasonable combinations of parameters

- Draw plots where you vary one parameter on the x-axis and see the behavior of the output variable on the y-axis.

Step 4: Simulate a full data set

Which input variables do your simulated participants bring to the experiment? Real participants bring variability in these variables.

Assume a specific distribution of all input variables that participants bring to the experiment. Even better: find empirical evidence for it, for example from existing open data sets or summary statistics from publications.

Maybe you need to transform the scale of the empirical variable into the scale of your simulated equivalent (e.g., via z-standardization).

Once all of these values are defined, simulate a sample of participants (with their starting values), and put half of them into the experimental group, and half of them into the control group. Use the resulting output values to computer a regular t-test.

Now the question is: Does the simulated model produce the effect? How large is the effect size? What happens if you change some of the functional parameters?