Applying VAST to an existing theory

Visual Argument Structure Tool (VAST) by Leising, Grenke & Cramer

Steps to formalize an existing verbal theory

Agenda for this presentation

- Step 1: Choose your starting point

- Step 2: Limit your scope

- Step 3: Collect robust empirical phenomena

- Step 4: Collect definitions of constructs, with reference to the literature.

- Step 5: Distill a (consensus or working) definition for each construct, add relationships

The full list of formalization steps is presented on this website. This slide set covers steps 2 to 6 of the broader scheme.

Step 1: Choose your starting point

- A: Narrative Theory Reconstruction (NTR)

- Starting point: The existing verbal theory.

- Main tasks: Read and understand the narrative theory, then formalize it. Check whether a simulation can produce the target phenomenon.

- Of only minor importance:

- Whether the phenomenon is actually robust.

- Do not fix inconsistencies, do not improve the theory: We want to make explicit what the original authors had in mind with their theory.

- This approach focuses on showing the gaps (without fixing them)

- B: Theory Construction Methodology (TCM)

- Starting point: A robust phenomenon.

- Main tasks:

- Understand the phenomenon (its robustness, evidence, moderating conditions, operationalizations; search for meta-analyses).

- Invent a new theory that can explain the phenomenon, or use an established theory from another domain and make necessary adjustments (could be within psychology, but also from completely different disciplines).

- Check whether a formal model of your theory produces the phenomenon.

- Of only minor importance: Any existing theory that aims to explain the phenomenon. You might compare your own formal model to existing theories later.

Step 1: Choose your starting point

A-B Mixture Model (for formalization attempts)

- Starting point is an existing narrative theory

- We soon will detect inconsistencies. For successfully modelling the theory, we have to resolve them, e.g. by:

- Deciding on one specific construct definition

- Synthesizing multiple definitions

- Only use robust phenomena as explanatory targets

- Select only components of the theory that are theoretically central to explain your explanatory target.

- The result will be a reduced and refined theory, that is inspired by the original theory but not identical to it.

- This approach is more about filling the gaps (instead of just showing them).

Step 2: Limit your scope

Most theories in psychology are too fuzzy and broad to be formalized in one round. We restrict the scope of the theory to keep modelling feasible:

- Define the scope of original literature that is used as basis for the formalization.

- Limit the number of phenomena that your model is supposed to explain. Focus on phenomena that are empirically robust.

- Limit the number of constructs and their relationships, add complexity later.

- Start with the smallest number of constructs necessary to explain your explanatory target.

- Maybe exclude entire sections of a theory.

- What is your focal outcome variable (DV)? What are the focal predictors or interventions?

Step 3: What is the explanatory target? Collect robust empirical phenomena

Step 3: Collect robust empirical phenomena

Robustness of phenomena has two dimensions:

- Generalizability (cf. UTOS framework): The effect has been shown for different Units, with different operationalizations of Treatments and Outcomes, and in multiple Settings.

- Strong empirical evidence for each/many of the generalizations.

Step 3: Collect robust empirical phenomena

Practically, you should do the following steps to assess these two dimensions:

- Search for meta-analyses that report on phenomena with our focal variables → Only if no meta-analysis is available, or it is not helpful: Do a broader literature search for primary studies.

- Assess the robustness of the phenomena along the two dimensions:

- How generalizable is it? Go through all four UTOS dimensions and evaluate which types of generalization have been shown across studies.

- How strong is the evidence? (e.g., based on number k of studies in a meta-analysis, strength of evidence, risk of bias)

- Write a paragraph that makes an overall assessment of the robustness of each phenomenon and gives a clear and explicit answer: “The phenomenon can (not) be considered robust because, …”. Refer to the two dimensions of robustness and give references that back up your claim.

Step 3: Collect robust empirical phenomena

How to jointly assess “strength of evidence” and “generalizability”

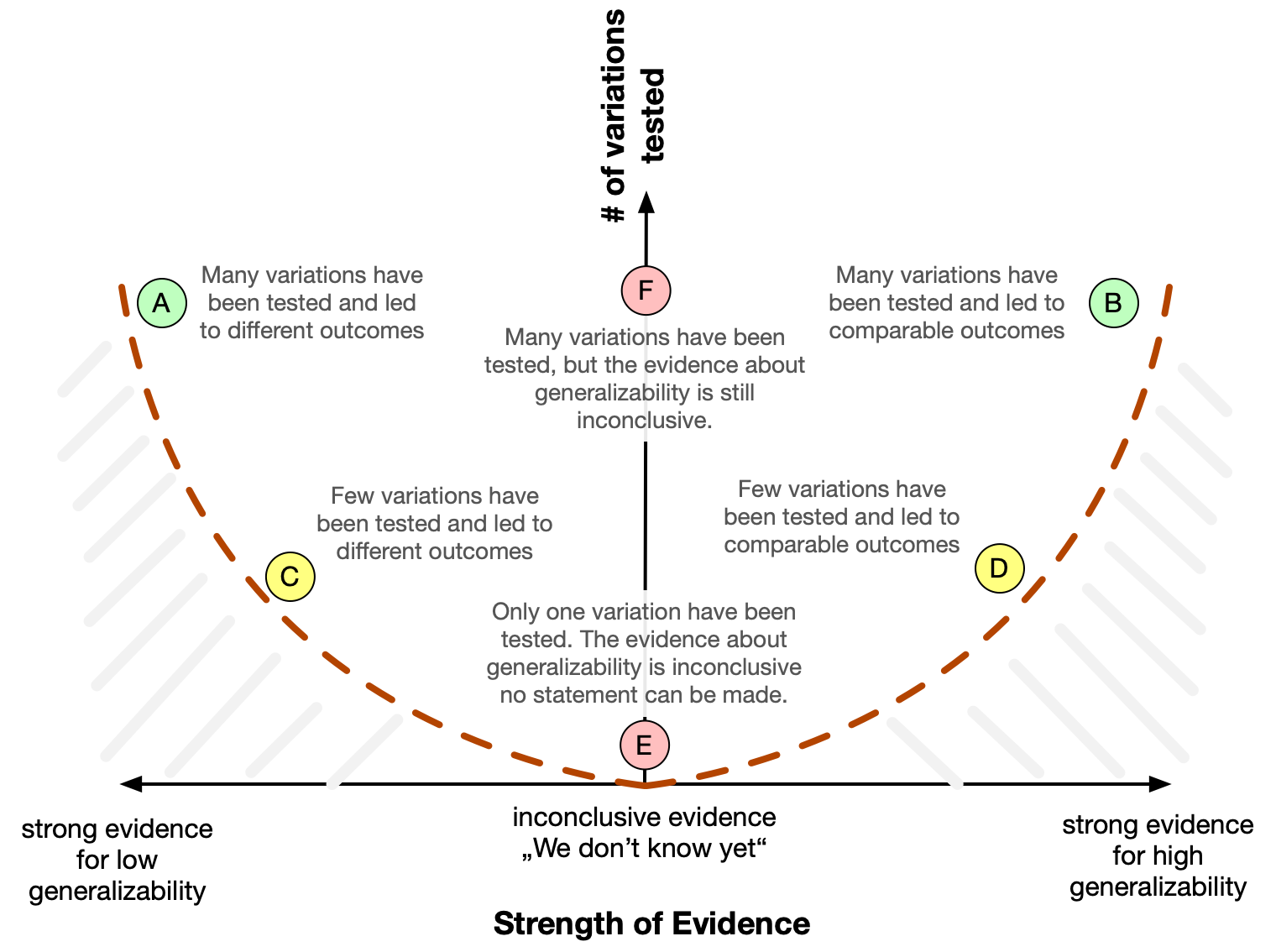

When you assess the generalizability, you should distinguish three prototypical epistemic states:

- “I know that it is generalizable.” → strong evidence for \(H_1\)

- “I know that it is not generalizable.” → strong evidence for \(H_0\)

- “I do not know whether it is generalizable or not - with the given empirical evidence I cannot answer this question.” → inconclusive evidence

When is the strength of evidence strong? If …

- you have many studies,

- which are methodologically sound (i.e., valid),

- and show (at least in sum) a decisive statistical result into either direction (i.e., either for a difference, or for a null effect)

Step 3: Collect robust empirical phenomena

General principle: We can only make statements about stuff that we actually studied.

We describe six prototypical examples:

- (A): strong evidence that the phenomenon is not generalizable.

- (B): strong evidence that the phenomenon is generalizable - at least within the space of sampled variations.

- (C): weak evidence that the phenomenon is not generalizable.

- (D): weak evidence that the phenomenon is generalizable. As we don’t know about the untested variations, the evidence principally cannot be very strong.

- (E): principally unknowable whether the result generalizes to other variations. We can only conclude that we cannot conclude anything about generalizability.

- (F): evidence is inconclusive. There are descriptive differences between variations, but they are small, and it is not clear if these differences are statistically significant and substantial.

Step 3: Collect robust empirical phenomena

Exercise (5 min)

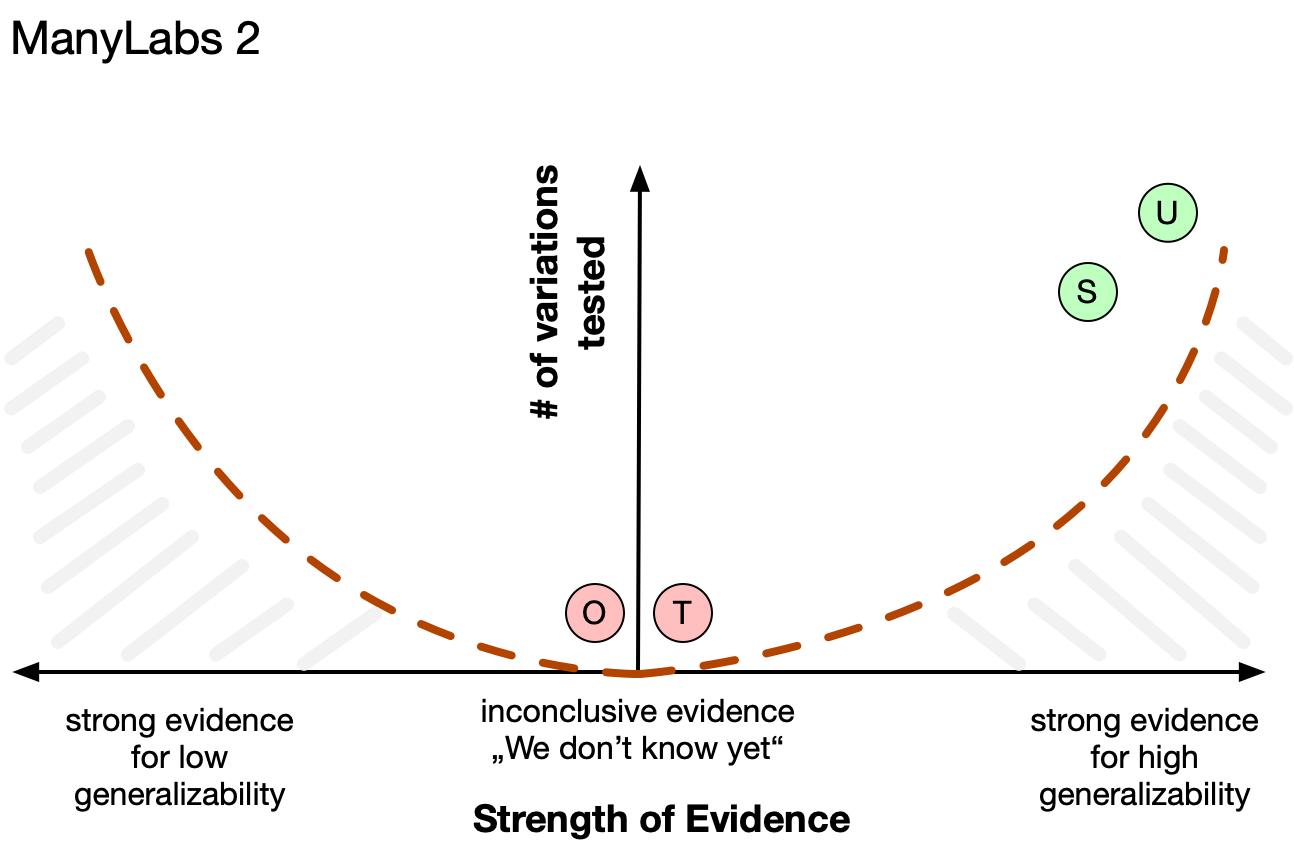

All four UTOS dimensions can get an independent assessment. Consider the ManyLabs2 study, where identical experiment (except translation of materials) has been administered online in very diverse samples (at least diverse with respect to nationality and cultural background).

Non-zero effects could be found with remarkably low variability across samples. Quoted from the abstract:

“Cumulatively, variability in the observed effect sizes was attributable more to the effect being studied than to the sample or setting in which it was studied”.

Evaluate the generalizability of the reported effects along the four UTOS dimensions.

Step 3: Collect robust empirical phenomena

Applying the heuristic to ManyLabs2

Hence, we have strong evidence for high generalizability for the U and the S dimension, but we cannot make a conclusion concerning the T and the O dimensions, as they lacked the necessary variation in the study.

Step 3: Collect robust empirical phenomena

Interlude: Elements of a theory

The elements of a theory are:

- concepts (i.e., categories or dimensions that are applicable to certain objects)

- relationships (typically causal) among these concepts

Step 4: Collect definitions of constructs

Construct Table

- Collect quotes of definitions of constructs and their relationships from the literature.

- Make them atomic (i.e., split up long quotes into their basic components).

- Assign a unique ID to each statement.

This table will be called the Construct Table, as it collects the original sources for the definitions of the constructs.

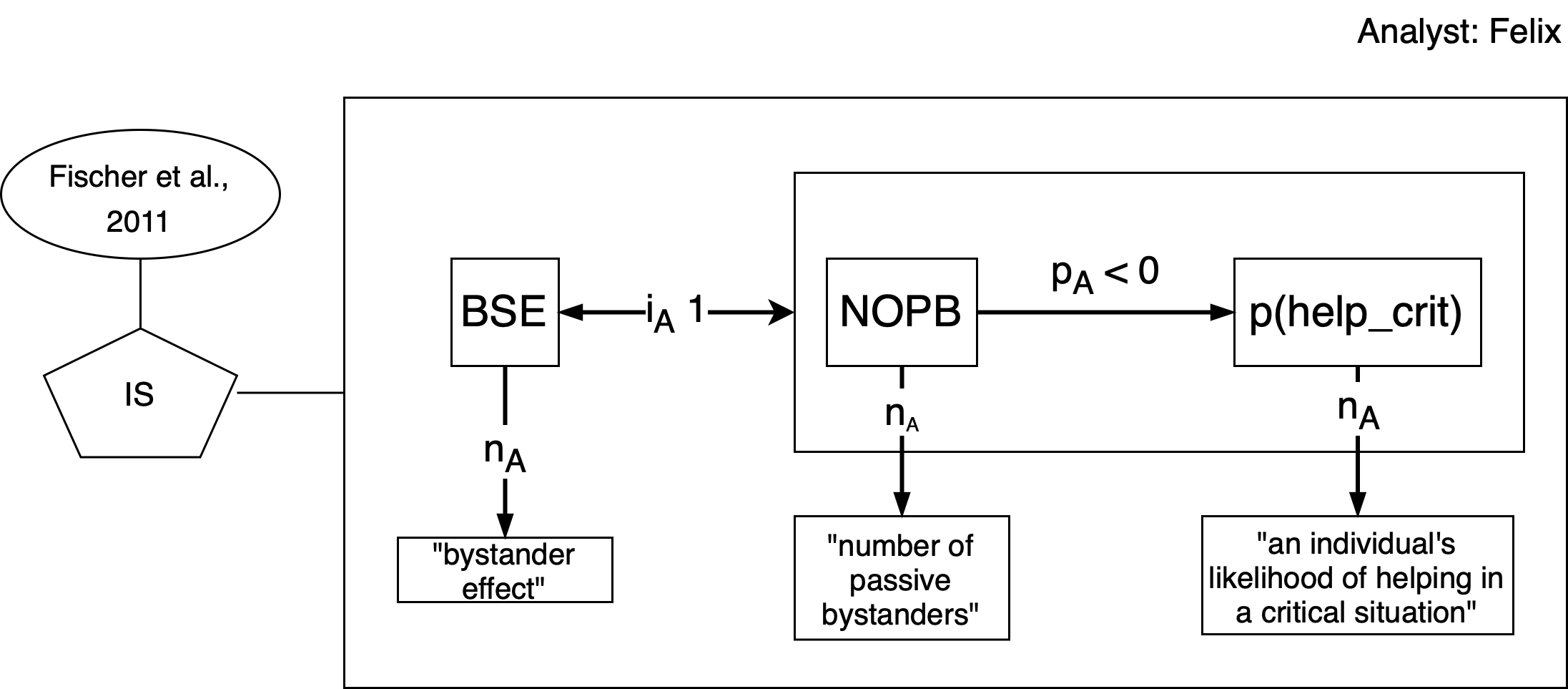

| Reference | Quote | Extracted element | Element type | Rel. type | Short name / associated concept | ID |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fischer et al. (2011), p. 517 | “The bystander effect refers to the phenomenon that an individual’s likelihood of helping decreases when passive bystanders are present in a critical situation.” | likelihood of helping | C | n | p(help) | A1 |

| number of passive bystanders | C | n | NOPB | A2 | ||

| critical situation | C | n | critSit | A3 | ||

| p(help) decreases when NOPB > 0, given critSit | HOC | p | bystander effect | A4 |

- Element Type is one of: Concept, Relationship, HOC: Higher-order Concept.

- Relationship Type: One of the VAST relationship types (n, p, i, r, c, …)

Step 5: Distill a working definition for each construct, add relationships

- Draw a VAST display with a naming (

n) relationship for each construct. - Use the ID from the Construct Table as subscript for each relationship. This way your claims in the VAST display can be easily backlinked to the original sources in the literature.

- The small “A” subscript indicates that all relationships in this display are derived from the quote with ID “A” in the Construct Table.

A useful standard setup for psychological theories

Sensors

Perceiving the environment

Organisms have a vast range of sensors for perceiving their environment. These have been adapted to selection pressures:

- Humans don’t have sensors for ultraviolet light (bees do)

- We have no sensors for radioactivity, as this was no relevant selective force

- Single-celled organism have, for example …

- chemoreceptors for sugar

- tactile sense (simple membranes transmitting changes in pressure)

Sensors

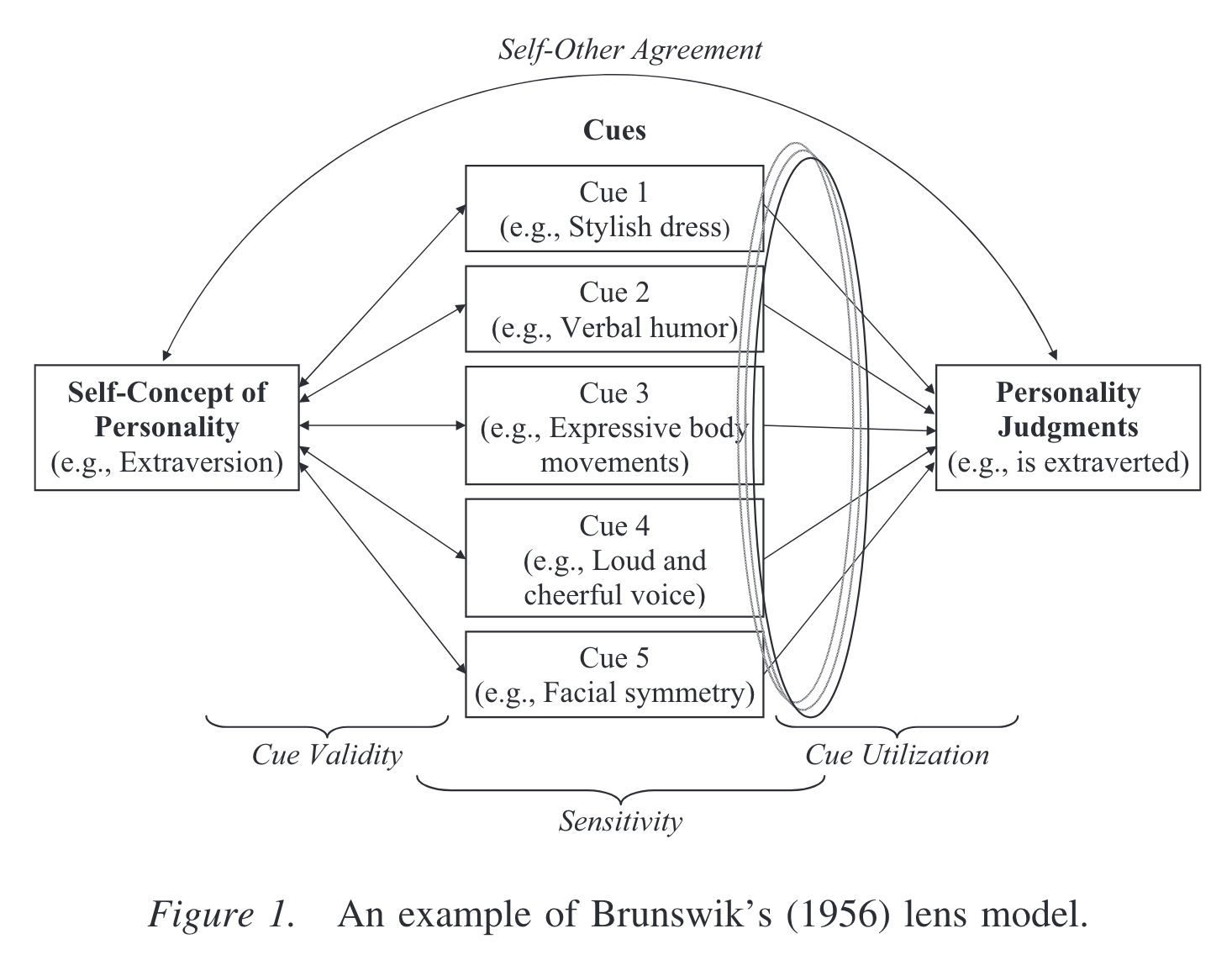

Brunswik’s lens model

- Organisms constantly need to form a judgement about latent properties of situations and objects (the criterion)

- Most criteria are not directly observable, but need to be inferred via cues. Example:

- Latent property: The caloric energy of a dessert

- Cues: Size, taste, color

- Cues often are not perfect indicators, but rather statistically correlated with the criterion.

Higher correlation → higher cue validity - Not all cues are used (with the same weight) in judgement formation → cue utilization

Sensors

Brunswik’s lens model

Sensors

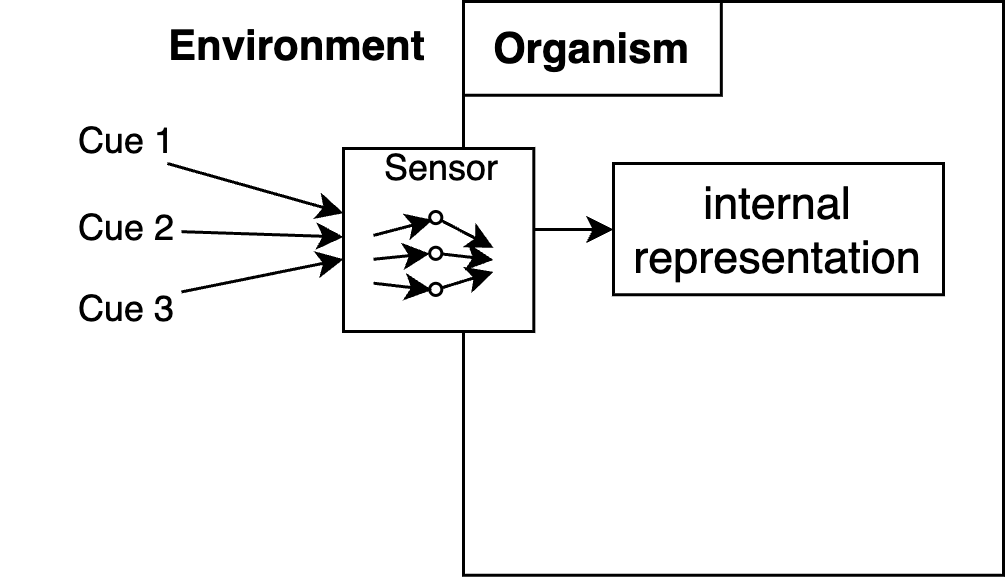

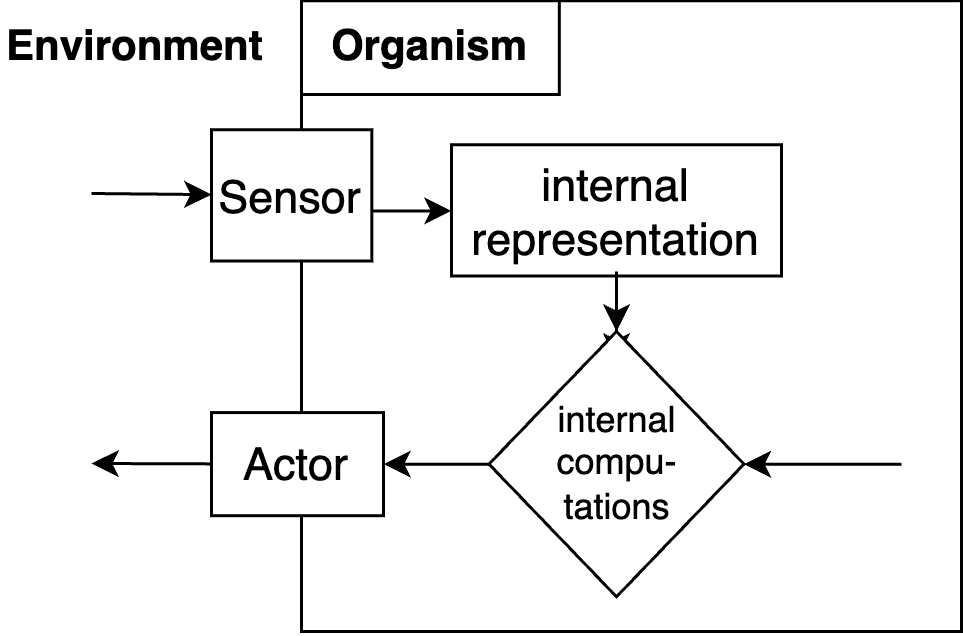

Implementing the lens model in a VAST display

Principle:

- Draw a box (“higher-order concept”) that represents an organism with its boundaries

- Any external information must enter the organism via a sensor

- Arrows going into a sensor must come from observable cues

- Arrows going out of sensors are the organism’s representation of the phenomenon in the environment

- The lens model (i.e., the weights of cue usage & utilization) is implemented in the sensor box

- No arrow may directly cross the organisms border\(*\)

Actors

Sensing the environment only makes sense when organisms are able to react on this information. Devices that allow to manipulate the environment (or the organism’s position within the environment) are called actors.